Abstract

We have reported that hydrogen (H(2)) acts as an efficient antioxidant by gaseous rapid diffusion. When water saturated with hydrogen (hydrogen water) was placed into the stomach of a rat, hydrogen was detected at several microM level in blood. Because hydrogen gas is unsuitable for continuous consumption, we investigated using mice whether drinking hydrogen water ad libitum, instead of inhaling hydrogen gas, prevents cognitive impairment by reducing oxidative stress. Chronic physical restraint stress to mice enhanced levels of oxidative stress markers, malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, in the brain, and impaired learning and memory, as judged by three different methods: passive avoidance learning, object recognition task, and the Morris water maze. Consumption of hydrogen water ad libitum throughout the whole period suppressed the increase in the oxidative stress markers and prevented cognitive impairment, as judged by all three methods, whereas hydrogen water did not improve cognitive ability when no stress was provided. Neural proliferation in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus was suppressed by restraint stress, as observed by 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation and Ki-67 immunostaining, proliferation markers. The consumption of hydrogen water ameliorated the reduced proliferation although the mechanistic link between the hydrogen-dependent changes in neurogenesis and cognitive impairments remains unclear. Thus, continuous consumption of hydrogen water reduces oxidative stress in the brain, and prevents the stress-induced decline in learning and memory caused by chronic physical restraint. Hydrogen water may be applicable for preventive use in cognitive or other neuronal disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress is widely accepted as a contributor to neuronal vulnerability (Langley and Ratan, 2004; Lin and Beal, 2006; Ohta and Ohsawa, 2006; Sayre et al, 2008). Thus, suitable antioxidants are desired to protect neural precursors and neurons against oxidative damage in the brain (Ferri et al, 2003); however, most antioxidants are not able to reach neurons because of the blood–brain barrier. We have recently reported that molecular hydrogen (H2) reduces oxidative stress (Ohsawa et al, 2007; Fukuda et al, 2007), and can penetrate the blood–brain barrier to protect neurons by gaseous diffusion; however, inhalation of hydrogen gas may be unsuitable as continuous hydrogen consumption for preventive use. A brief report has suggested that consumption of water containing hydrogen at a saturated level (hydrogen water) reduces oxidative stress in rats, as shown by decreased levels of urine oxidized guanine and hepatic lipid peroxide (Yanagihara et al, 2005). Thus, we examined the effect of hydrogen water on cognitive decline induced by oxidative stress.

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis may be involved in cognitive functions, including learning and memory, and spatial recognition (Abrous et al, 2005; Bruel-Jungerman et al, 2007). Antidepressants increase adult neurogenesis (Dranovsky and Hen, 2006; Becker and Wojtowicz, 2007; Sahay and Hen, 2007), suggesting that suppression of adult neurogenesis may be responsible for some mental disorders. Here we show that when chronic physical stress was applied to mice continuous consumption of hydrogen water reduced oxidative stress in the brain, and prevented the decline in the proliferation of progenitor neural cells and the impairment of cognitive function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hydrogen Water

Molecular hydrogen (H2) was dissolved in water under high pressure (0.4 MPa) to a supersaturated level using hydrogen water-producing apparatus (ver. 2) produced by Blue Mercury Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). The saturated hydrogen water (500 ml) was stored under atmospheric pressure in an aluminum bag with no dead volume. Hydrogen water was freshly prepared every week, which ensured that a concentration of more than 0.6 mM was maintained. We confirmed the hydrogen content with a hydrogen electrode (ABLE). Each day, hydrogen water from the aluminum bag was placed into a closed glass vessel (70 ml) equipped with an outlet line having two ball bearings, which kept the water from being degassed. This vessel ensured that the hydrogen concentration was more than 0.4 mM after 1 day. Hydrogen water degassed by gentle stirring was used for control animals; the complete removal of hydrogen gas was confirmed with the hydrogen electrode.

Measurement of Hydrogen in Blood

Hydrogen water (3.5 ml at 0.8 mM) was placed into the stomach of a rat (approximately 230 g) by a catheter. After 3 min, 5 ml of venous blood was collected from the heart and placed into a small aluminum bag containing 25 ml air. After hydrogen gas from blood was transferred into the air, 20 ml of the air from the aluminum bag was applied to gas chromatography to examine the content of hydrogen as described (Ohsawa et al, 2007).

Malondialdehyde Measurement

Brain malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were determined using a Bioxytech MDA-586 Assay Kit (OxisResearch, Oregon). Briefly, the frozen left brains were homogenized in the presence of butylated hydroxytoluene. After centrifugation, free MDA in the supernatant was converted to a stable carbocyanine dye (maximum absorption at 586 nm) by chemical reaction with N-methyl-2-phenylindole. MDA levels were normalized against protein concentration.

Physical Restraint Stress

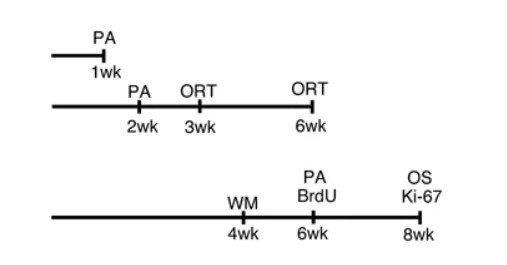

This study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nippon Medical School. We obtained ICR mice, 7 weeks of age (33–34 g body weight), from CLEA Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), and divided 40 mice into four groups (each group had 10 mice) by the following combination. Stress and CTL: groups with and without restraint stress, respectively. HW(+) and HW(−): groups given water with and without hydrogen, respectively. Each mouse was placed in a 3 × 3 × 7.5 cm stainless-steel cage, which completely restricted their movement, but allowed them to drink water ad libitum. Immobilization stress was given 10 h per day (0900–1900 hours) for 6 days each week. Each immobilized mouse was housed individually in a small 10 × 10 × 10 cm compartment of a multicompartment cage for the remaining time to avoid aggression and to prevent social isolation. Hydrogen water or degassed water was available ad libitum throughout the whole period. Unstressed mice were housed in standard-sized cages consisting five mice per cage, and they were handled daily without stress. Schedules for providing restraint stress and performing experiments are schematically illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Schedules for subjecting mice to restraint stress and performing experiments are illustrated. Single bar indicates a series of experiments using the same mice. PA, ORT, WM, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU), Ki-67, and OS indicate the time points for passive avoidance, object recognition test, Morris water maze, injection of BrdU, and sampling for Ki-67 and oxidative stress (4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) staining and malondialdehyde (MDA) measurement). During the experiments of the Morris water maze, mice continued to be immobilized for 8 h per day.

Passive Avoidance Learning

The apparatus consisted of two compartments, one light and the other dark, separated by a vertical sliding door (O’Riordan et al, 2006). We initially placed a mouse in the light compartment for 20 s. After the door was opened, the mouse could enter the dark compartment (mice instinctively prefer being in the dark). After the mouse entered the dark compartment, the door was closed. After 20 s, the mouse was given a 0.3 mA electric shock for 2 s. The mouse was allowed to recover for 10 s, and was then returned to the home cage. After 24 h, the mouse was again placed in the lighted section with the door opened to allow the mouse to move into the dark section. We scored the latency time for stepping through the door. In addition, the number of mice that stayed in the light section for more than 300 s was recorded.

Object Recognition Task

The novel-object recognition and memory retention test was used to examine recognition memory (Wang et al, 2004; De Rosa et al, 2005). A mouse was habituated in a cage for 4 h, and then two different-shaped objects were presented to the mouse for 10 min as training. The number of times of explorations and/or sniffs of one object, which will be replaced with a novel one, was counted for the initial 5-min period (Training). To test memory retention after 1 day, one of the original objects was replaced with the novel one with a different shape, and then the number of times of explorations and/or sniffs of the novel one was counted for 5 min (Retention test). The recognition index was obtained as the frequencies (%) of exploring and/or sniffing the original object or the novel one.

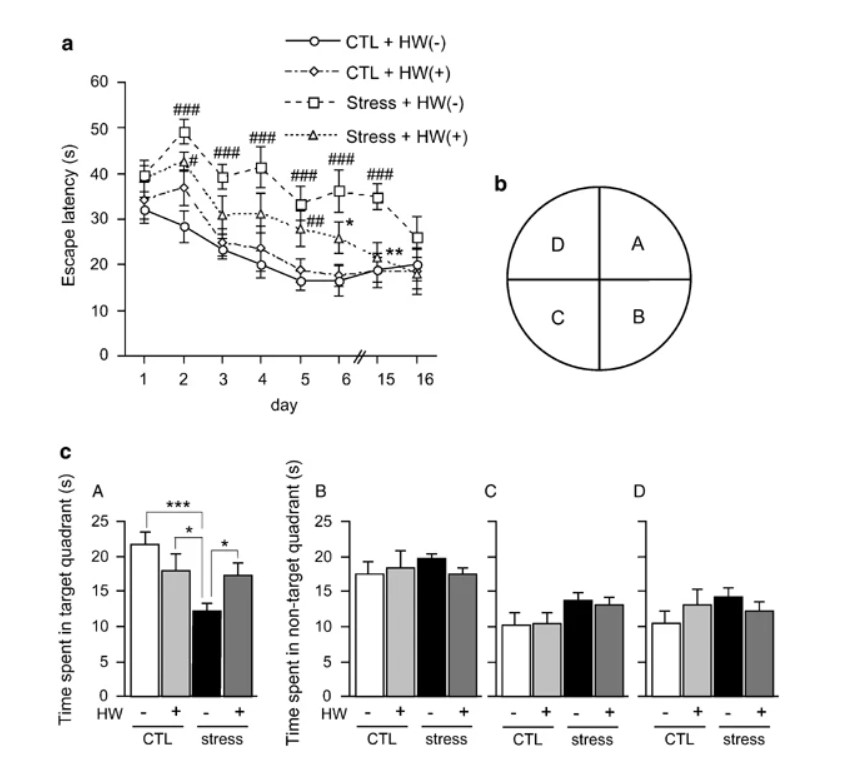

Spatial Learning

Mice were trained on the Morris water maze (Morris et al, 1982; D’Hooge and De Deyn, 2001), with four trials per day over 6 days. The water maze was a circular pool filled with water at room temperature (diameter, 125 cm; height, 55 cm; water temperature, 24±1°C). A transparent platform (diameter, 10 cm) was hidden 1 cm below the surface of water that had been made opaque with white nontoxic paint. Starting points were changed every day. Each trial lasted until either the mouse had found the platform or for a maximum of 60 s. The examiner determined the time of swimming until the mouse reached the platform (latency) using a stopwatch and a video. All mice were allowed to rest on the platform for 20 s. The platform was removed for a probe trial 24 h after the last training session on day 6. Retention of the spatial training was assessed 1 h after the last training trial. The single-probe trial consisted of a 60 s free swim in the pool without the platform. Mice were placed and released opposite the site where the platform had been located and the time spent in each quadrant was recorded for the probe trial. During the experiments, mice continued to be immobilized for 8 h per day, instead of 10 h.

Immunohistochemistry

After 8-week restraint stress, mice were perfused transcardially with saline under anesthesia. The right brain hemisphere and the hemicerebellum were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4) for 24 h at room temperature. Coronal sections (40 μm) were cut rostrocaudally with a vibratome (Leica, Cambridge, UK) and immersed in PBS.

For 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) immunohistochemistry, BrdU (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl and sterilized by filtration. After 6-week restraint stress, the mice received one intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg body weight at a concentration of 10 μg/ml per day for 5 consecutive days as described (Wolf et al, 2006). The sections were incubated in 2 N HCl at 37°C for 30 min to denature DNA, further incubated in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min, and then blocked with mouse Ig blocking reagent from the M.O.M. kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h. The primary antibody used was mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU (BD Pharmingen, 1 : 100).

For Ki-67 and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) immunoreactions, after 8-week restraint stress, sections were incubated in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 90°C for 5 min, left to cool at room temperature, further incubated in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min at 37°C, and then blocked with the M.O.M. kit and normal goat serum from the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories), respectively. The primary antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal anti-Ki-67 antibody (Abcam, 1 : 500) and mouse monoclonal anti-HNE antibody (20 μg/ml; JaICA, Fukuroi, Japan). The HNE secondary antibody (M.O.M. biotinylated anti-mouse IgG, 1 : 250; Vector Laboratories) and the BrdU and Ki-67 secondary antibodies (biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG, 1 : 200) were applied for 2 h. The avidin/biotinylated mouse peroxidase complex (ABC kit; Vector Laboratories) was applied for 2 h, and the sections were stained with 3′3-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) for 1 min.

Wire-Hanging Test

After 6-week restraint stress, neuromuscular strength was tested by wire-hanging test (Hamann et al, 2003). In brief, mice were placed on wire netting, which was lightly shaken, causing the mouse to grip the wire. After the 20-s cutoff time, the wire netting was turned upside down (180°) and the time to falling was recorded.

Open-Field Test

After 7-week restraint stress, for the open-field test (Kim and Han, 2006), locomoter activity was measured in the open field of a white Plexiglas chamber (36 × 30 × 18 cm). Each mouse was individually placed in the left corner of an open field and locomotion was recorded for the indicated period. Horizontal locomotor activity was assessed according to the total rearing score for 20 min.

Statistical Analysis

All values are shown as the mean±standard error of measurement (SEM). Differences between groups were analyzed using one- or two-way ANOVA. When statistical differences were found, Fisher’s PLSD post hoc test was performed. Statistical significance was accepted as P<0.05. All the experiments were examined in a blinded fashion.

RESULTS

Physical Restraint Stress Enhanced Oxidative Stress and Hydrogen Water Decreased it

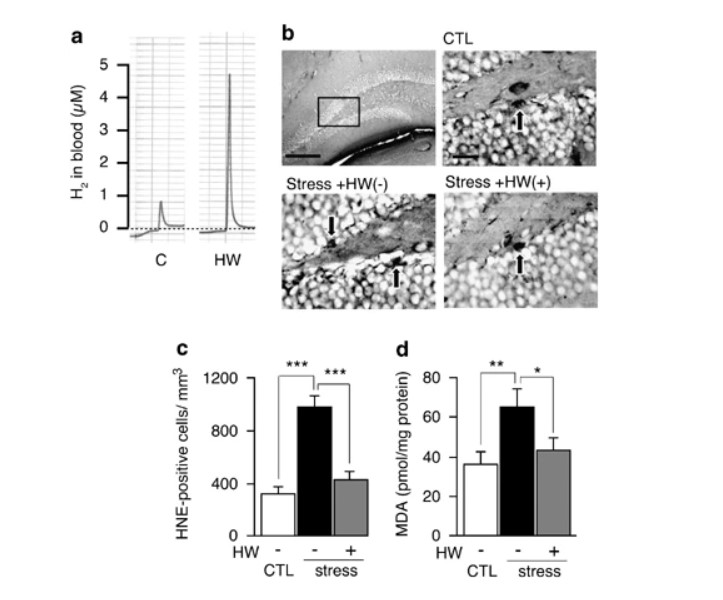

First, we examined whether hydrogen can be sufficiently incorporated into a body by drinking hydrogen water. Because it is difficult to obtain a sufficient volume of blood from mice, we used rats for the measurement of hydrogen concentration in the blood. We placed saturated hydrogen water at 3.5 ml per 230 g (15 ml/kg) directly into the stomach of a rat by a catheter. After 3 min, hydrogen was detected in the blood at the level of 5 μM (Figure 2a). Alternatively, an unpublished result suggests that the half-span of hydrogen in the muscle of rats is approximately 20 min as monitored with a needle-type hydrogen electrode, after the administration of hydrogen gas (data not shown).

Figure 2

Consumption of hydrogen water reduced oxidative stress enhanced by restraint stress. (a) Hydrogen (H2) in blood was measured 3 min after hydrogen water (3.5 ml) was placed directly into the stomach of a rat by a catheter. Profiles of gas chromatography are shown. (b) After 8-week exposure to restraint stress, the hippocampus region was stained with anti-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE)-conjugated peptide antibody. Representative photographs of HNE staining are shown. Arrows indicate positive cells. Scale bar: upper left panel, 100 μm; magnified panels, 25 μm. (c) HNE-positive cells in the dentate gyrus were counted using four serial sections (F(2, 27)=28.031; P<0.0001). (d) Malondialdehyde in the whole brain was biochemically measured (F(2, 27)=4.177; P=0.0263). CTL, unstressed control group; Stress, group exposed to restraint stress for 8 weeks; HW(+), group provided with hydrogen water; and HW(−), group provided with degassed water. Data are shown as the mean±SEM (each group consisted 10 mice). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001 vs Stress+HW(−).

We used mice for experiments of restraint stress. To examine whether mice preferably drank hydrogen water, we measured the volume of water consumed ad libitum by mice. The volume of water drunk by each mouse was nearly the same between groups drinking hydrogen water and degassed water (3.77±0.11 vs 3.75±0.08 ml, SEM).

Each mouse was then subjected to chronic physical restraint stress by placing it alone for 10 h per day in a very small cage, which completely restricted its movement, but allowed it to drink water ad libitum, and then was housed for 14 h in a small compartment as described in ‘Materials and methods’. These treatments continued for 6 days per week. Water was available ad libitum throughout the whole period.

We examined the level of oxidative stress in the brain by immunohistologically estimating HNE, an end product of lipid peroxide (Ohsawa et al, 2003) after 8-week restraint stress (Figure 2b, c). Another oxidative marker, MDA, was estimated using a biochemical method (Fukuda et al, 2007; Figure 2d). These results revealed that chronic restraint stress enhanced oxidative stress in the brain. Notably, the consumption of hydrogen water suppressed the accumulation of the oxidative stress markers (Figure 2b–d).

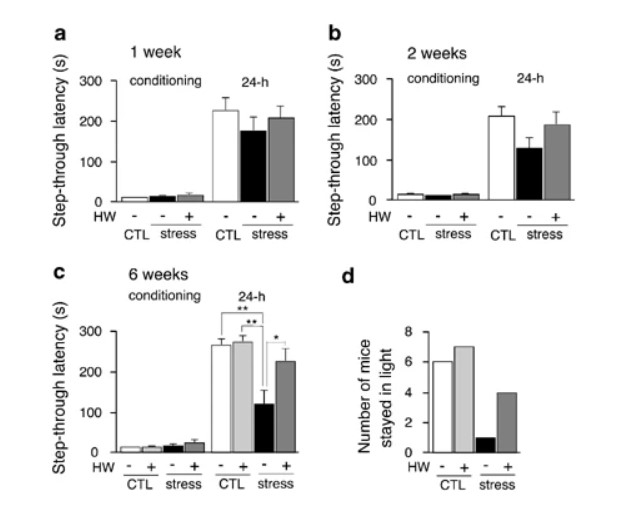

Passive Avoidance Learning, Novel Recognition Test, and Morris Water Maize

We examined learning and memory ability using the passive avoidance test (O’Riordan et al, 2006). Mice instinctively prefer a dark compartment; however, if an electric shock is given in the dark compartment, the mice are normally reluctant to reenter it. At 1 or 2 weeks after restraint stress, the memory of the electric shock tended to be lost in mice provided with control degassed water (Figure 3a, b). On the other hand, mice that were provided with hydrogen water ad libitum showed a trend toward improved learning and memory (Figure 3a, b). Six-week restraint stress significantly impaired learning and memory in mice consuming no hydrogen water, whereas consuming hydrogen water ad libitum significantly ameliorated or prevented the cognitive impairment induced by restraint stress (Figure 3c, left panel). In particular, more mice (fourfold) stayed in the light section for more than 300 s than control group without hydrogen (Figure 3c, right panel). On the other hand, consumption of hydrogen water did not improve the cognitive ability when no stress was provided (Figure 3c).

Figure 3

Passive avoidance test shows that hydrogen water prevented cognitive decline induced by restraint stress. After applying restraint stress for 1 week (a), 2 weeks (b), and 6 weeks (c) (F(3, 36)=7.661; P<0.0005), the passive avoidance test was performed by examining step-through latency time from light to dark compartments on the first day of the conditional trial (conditioning). At 24 h after an electric shock was given in the dark compartment, the latency time of mice moving from the light to dark compartment was measured (24 h). When a mouse did not enter the dark compartment for 300 s, the latency time was scored as 300 s. The number of mice that stayed in the light compartment for more than 300 s on the second day is shown (right panel). Stress and CTL, groups with or without restraint stress, respectively; HW(+) and HW(−), groups given water with and without hydrogen, respectively. Experiments in (a), (b), and (c) were performed using different mice. *P<0.01 and **P<0.001 vs Stress+HW(−). Data are the mean±SEM (each group consisted 10 mice).

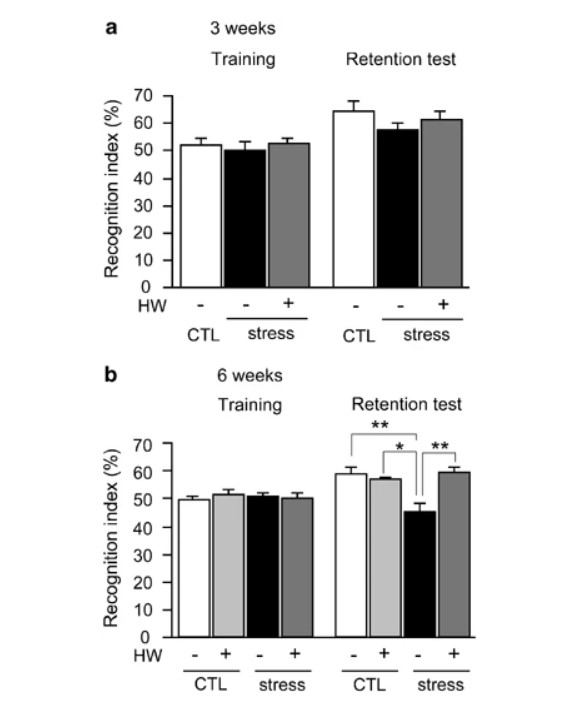

As an alternative method to confirm impaired cognitive function after restraint stress, we applied the object recognition task (Wang et al, 2004; De Rosa et al, 2005; Ohsawa et al, 2008). If mice remember an object, they prefer to explore and/or sniff a novel object when the original object is replaced with the novel object. After 3-week restraint stress, hydrogen water tended to prevent or restore the decline in the recognition of a novel object, observed as a decreased frequency of exploring or sniffing the novel object (Figure 4a). The mice were subjected to the second object recognition task after 6-week stress, because the second test was available if the second objects were completely different from ones used in the first examination (Mouri et al, 2007). When restraint stress was applied for 6 weeks, consuming hydrogen water ad libitum significantly prevented or restored the decline in recognition and memory (Figure 4b). It should be noted that consumption of hydrogen water could not improve the cognitive ability when no stress was provided (Figure 4b).

Figure 4

Object recognition task shows that hydrogen water prevented cognitive decline induced by restraint stress. For the object recognition task, after applying restraint stress for 3 (a) or 6 weeks (b) (F(3, 35)=7.466; P<0.0005), two different objects were presented to a mouse for 10 min for visual training and the number of times of explorations and/or sniffs of an object was counted in the initial 5-min period (Training). To test memory retention after 1 day, one of the original objects was replaced with the novel one with a different shape, and then the number of times of explorations and/or sniffs of the novel one was counted for 5 min (Retention test). The recognition indexes were obtained as the frequency (%) of exploring and/or sniffing the object that will be replaced, or the novel one that had been replaced. For example, if a mouse explored and/or sniffed only the novel object, the recognition index is scored as 100%, whereas if it did only the unchanged one, the recognition index is 0%. Stress and CTL, groups with or without restraint stress, respectively; HW(+) and HW(−), groups given water with and without hydrogen, respectively. Experiments in (a) and (b) were performed using the same mice. When the second object recognition test was given to the same mice, objects that differed in shape and color were used. Data are the mean±SEM (each group consisted 10 mice). *P<0.01 and **P<0.001 vs Stress+HW(−).

Figure 5

Hydrogen Water did not Affect Stress-Induced Reductions in Muscular Strength and Movement

To examine whether hydrogen water influenced the whole body, we monitored body weight during periods of restraint stress. Body weight decreased with restraint, and hydrogen water did not overcome this decrease (Supplementary Figure S1). Wire-hanging (Hamann et al, 2003) and open-field tests (Kim and Han, 2006) were used to exclude the possibility that hydrogen water influenced muscular strength and movement. Wire-hanging times depended on the body weight of each mouse, and no significant difference was observed in muscular strength (Supplementary Figure S2). Although restraint stress tended to affect movement, no effect of hydrogen water consumption was observed in the locomotion test (Supplementary Figure S3). Together, the behaviors observed by the three methods used to test cognitive function were not due to changes in movement ability, but indicated a decline in learning and memory. Thus, the improvement observed in the hydrogen water group was reflected by better learning ability and memory (Figures 3, 4, 5).

Hydrogen Water Improved the Proliferation of Progenitor Cells

Cognitive function may be involved in adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Finally, after 8-week restraint stress, we examined the correlation between adult neurogenesis and the hippocampal function by counting proliferating progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus with BrdU labeling (Kee et al, 2002; Ekdahl et al, 2003). Positive nuclei, as judged by the shape and size, were counted in the boundary region of the dentate gyrus in four serial sections. Restraint stress decreased the number of proliferating cells, and hydrogen water significantly restored them (Figure 6a, b). As an alternative method, Ki-67 was used as a marker of proliferating cells (Kee et al, 2002; Shidara et al, 2005). The results were similar to those obtained by the BrdU-labeling method (Figure 6c, d). These findings suggest that continuous consumption of hydrogen water improves the proliferation of neural progenitor cells or adult neurogenesis impaired by restraint stress.

Figure 6

DISCUSSION

In summary, the continuous consumption of hydrogen water throughout the whole period of physical restraint stress reduced oxidative stress, prevented the decline in the proliferation of neural progenitors, and prevented cognitive decline, all of which are induced by chronic physical restraint stress. The restraint stress applied in this study may also induce considerable psychological as well as physical stress. In this study, we examined impaired learning and memory by three different methods: passive avoidance learning, object recognition task, and the Morris water maze. In these methods, successive object recognition tasks are available (Mouri et al, 2007) and the Morris water maze gives no influence on results of passive avoidance test (Yamada et al, 1999; King and Arendash, 2002). Thus, some experiments were performed using the same mice as shown in Figure 1, although a possibility cannot be ruled out that the passive avoidance test was influenced by the water-maze training.

We have recently reported that hydrogen reduced hydroxyl radicals, the most reactive oxygen species (ROS), and protected cells against oxidative stress. Inhalation of 1% hydrogen gas was enough to protect the brain and liver (Ohsawa et al, 2007; Fukuda et al, 2007), where the hydrogen in blood should be 8 μM because the saturated level of hydrogen reached 800 μM under atmospheric pressure. It is possible that continuous consumption of hydrogen defends the brain against chronic oxidative stress even at much lower concentrations than 8 μM. In this study, we showed that the incorporation of hydrogen from the stomach into blood reached 5 μM. Continuous exposure to hydrogen may change blood components toward the reductive state, and indirectly influence the oxidative state in the brain. Although it remains unclear how hydrogen reduces oxidative stress in the brain, the present study may highlight the prominent role of oxidative stress in deficits of learning and memory.

The consumption of hydrogen water ameliorated the proliferation of neural progenitors that had been declined by restraint stress although the mechanistic link between the changes in neurogenesis and cognitive impairments is at this stage correlative. However, adult neurogenesis may be involved in hippocampal functioning, including learning and memory and spatial recognition processes, and affected by multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors. For example, adult neurogenesis is suppressed by cranial radiotherapy, stress-sensitive adrenal hormones such as glucocorticoids, and physical or psychological stress, and improved with inflammatory blockade. When we studied oxidative stress, we found growing evidence suggesting that it is involved downstream of contributors that affect adult neurogenesis: (1) radiotherapy produces hydroxyl radicals of ROS (Madsen et al, 2003; Raber et al, 2004, 2) an inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis, which may be elucidated by decreasing inflammatory oxidative stress (Ekdahl et al, 2003; Monje et al, 2003, 3) glucocorticoids enhance oxidative stress-induced cell death in the hippocampus (Behl et al, 1997), and (4) the present study and others have shown that restraint stress itself enhances oxidative stress in the brain (Liu et al, 1996; Kim et al, 2005; Luo et al, 2005).

Thus, it is possible that during the exposure to physical restraint stress continuous consumption of hydrogen water reduced oxidative stress in the brain, resulting in the improvement of adult neurogenesis or the stimulation of neural proliferation, leading to the prevention of the decline in learning and memory. This is the first report showing a benefit of drinking hydrogen water. Thus, we propose that hydrogen water is applicable as preventive treatment by reducing oxidative stress.

References

- Abrous DN, Koehl M, Le Moal M (2005). Adult neurogenesis: from precursors to network and physiology. Physol Rev 85: 523–569.CAS Google Scholar

- Becker S, Wojtowicz JM (2007). A model of hippocampal neurogenesis in memory and mood disorders. Trends Cogn Sci 11: 70–76.Article Google Scholar

- Behl C, Lezoualc’h F, Trapp T, Widmann M, Skutella T, Holsboer F (1997). Glucocorticoids enhance oxidative stress-induced cell death in hippocampal neurons in vitro. Endocrinology 138: 101–106.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Bruel-Jungerman E, Rampon C, Laroche S (2007). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity and memory: facts and hypotheses. Rev Neurosci 18: 93–114.CAS Article Google Scholar

- D’Hooge R, De Deyn PP (2001). Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain Res Rev 36: 60–90.Article Google Scholar

- De Rosa R, Garcia AA, Braschi C, Capsoni S, Maffei L, Berardi N et al (2005). Intranasal administration of nerve growth factor (NGF) rescues recognition memory deficits in AD11 anti-NGF transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 3811–3816.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Dranovsky A, Hen R (2006). Hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation by stress and antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry 59: 1136–1143.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Ekdahl CT, Claasen JH, Bonde S, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O (2003). Inflammation is detrimental for neurogenesis in adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13632–13637.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Ferri P, Cecchini T, Ciaroni S, Ambrogini P, Cuppini R, Santi S et al (2003). Vitamin E affects cell death in adult rat dentate gyrus. J Neurocytol 32: 1155–1164.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Fukuda K, Asoh S, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto Y, Ohsawa I, Ohta S (2007). Inhalation of hydrogen gas suppresses hepatic injury caused by ischemia/reperfusion through reducing oxidative stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 28: 670–674.Article Google Scholar

- Hamann M, Meisler MH, Richter A (2003). Motor disturbances in mice with deficiency of the sodium channel gene Scn8a show features of human dystonia. Exp Neurol 184: 830–838.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Kee N, Sivalingam S, Boonstra R, Wojtowicz JM (2002). The utility of Ki-67 and BrdU as proliferative makers of adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Methods 30: 97–105.Article Google Scholar

- Kim KS, Han PL (2006). Optimization of chronic stress paradigms using anxiety- and depression-like behavioral parameters. J Neurosci Res 83: 497–507.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Kim ST, Choi JH, Chang JW, Kim SW, Hwang O (2005). Immobilization stress causes increases in tetrahydrobiopterin, dopamine, and neuromelanin and oxidative damage in the nigrostriatal system. J Neurochem 95: 89–98.CAS Article Google Scholar

- King DL, Arendash GW (2002). Behavioral characterization of the Tg2576 transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease through 19 months. Physiol Behav 75: 627–642.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Langley B, Ratan RR (2004). Oxidative stress-induced death in the nervous system: cell cycle dependent or independent? J Neurosci Res 77: 621–629.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Lin MT, Beal MF (2006). Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443: 787–795.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Liu J, Wang X, Shigenaga MK, Yeo HC, Mori A, Ames BN (1996). Immobilization stress causes oxidative damage to lipid, protein, and DNA in the brain of rats. FASEB J 10: 1532–1538.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Luo C, Xu H, Li XM (2005). Quetiapine reverses the suppression of hippocampal neurogenesis caused by repeated restraint stress. Brain Res 1063: 32–39.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Madsen TM, Kristjansen PE, Bolwing TG, Wortwein G (2003). Arrested neuronal proliferation and impaired hippocampal function following fractionated brain irradiation in the adult rat. Neuroscience 119: 635–642.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Monje ML, Toda H, Palmer TD (2003). Inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science 302: 1760–1765.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O’Keefe J (1982). Place navigation impaired rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature 297: 681–683.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Mouri A, Noda Y, Hara H, Mizoguchi H, Tabira T, Nabeshima T (2007). Oral vaccination with a viral vector containing Abeta cDNA attenuates age-related Abeta accumulation and memory deficits without causing inflammation in a mouse Alzheimer model. FASEB J 21: 2135–2148.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Ohsawa I, Ishikawa M, Takahashi K, Watanabe M, Nishimaki K, Yamagata K et al (2007). Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat Med 13: 688–694.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Ohsawa I, Nishimaki K, Murakami Y, Suzuki Y, Ishikawa M, Ohta S (2008). Age-dependent neurodegeneration accompanying memory loss in transgenic mice defective in mitochondrial ALDH2 activity. J Neurosci 28: 6239–6249.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Ohsawa I, Nishimaki K, Yasuda C, Kamino K, Ohta S (2003). Deficiency in a mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase increases vulnerability to oxidative stress in PC12 cells. J Neurochem 84: 1110–1117.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Ohta S, Ohsawa I (2006). Dysfunction of mitochondria and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: on defects in the cytochrome c oxidase complex and aldehyde detoxification. J Alzheimers Dis 9: 155–166.Article Google Scholar

- O’Riordan KJ, Huang IC, Pizzi M, Spano P, Boroni F, Egli R et al (2006). Regulation of nuclear factor kappaB in the hippocampus by group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci 26: 4870–4879.Article Google Scholar

- Raber J, Rola R, LeFevour A, Morhardt D, Curley J, Mizumatsu S et al (2004). Radiation-induced cognitive impairments are associated with change in indicators of hippocampal neurogenesis. Radiat Res 162: 39–47.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Sahay A, Hen R (2007). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat Neurosci 10: 1110–1115.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Sayre LM, Perry G, Smith MA (2008). Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Chem Res Toxicol 21: 172–188.Article Google Scholar

- Shidara Y, Yamagata K, Kanamori T, Nakano K, Kwong JQ, Manfredi G et al (2005). Positive contribution of pathogenic mutations in the mitochondrial genome to the promotion of cancer by prevention from apoptosis. Cancer Res 65: 1655–1663.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Yamada K, Tanaka T, Han D, Senzaki K, Kameyama T, Nabeshima T (1999). Protective effects of idebenone and alpha-tocopherol on beta-amyloid-(1-42)-induced learning and memory deficits in rats: implication of oxidative stress in beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in vivo. Eur J Neurosci 11: 83–90.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Yanagihara T, Arai K, Miyamae K, Sato B, Shudo T, Yamada M et al (2005). Electrolyzed hydrogen saturated water for drinking use elicits an antioxidative effect: a feeding test with rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 69: 1985–1987.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Wang H, Ferguson GD, Pineda VV, Cundiff PE, Storm DR (2004). Overexpression of type-1 adenylyl cyclase in mouse forebrain enhances recognition memory and LTP. Nat Neurosci 7: 635–642.CAS Article Google Scholar

- Wolf SA, Kronenberg G, Lehmann K, Blankenship A, Overall R, Staufenbiel M et al (2006). Cognitive and physical activity differently modulate disease progression in the amyloid precursor protein (APP)-23 model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 60: 1314–1323.CAS Article Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Japanese Ministries of Health, Labour, and Welfare (H-18-Choju-009, Longevity Science) and Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (19659331).

Author information

Affiliations

- Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Institute of Development and Aging Sciences, Graduate School of Medicine, Nippon Medical School, Kawasaki, JapanKazufumi Nagata, Naomi Nakashima-Kamimura, Ikuroh Ohsawa & Shigeo Ohta

- Department of Health and Sports Science, Nippon Medical School, Kawasaki, JapanToshio Mikami

- Center of Molecular Hydrogen Medicine, Institute of Development and Aging Sciences, Nippon Medical School, Kawasaki, JapanIkuroh Ohsawa

Corresponding author

Additional information

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr Ohta is a director of Mitos Co. Ltd (Kawasaki, Japan), and a scientific adviser to Blue Mercury Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Blue Mercury Inc. supplied the fresh hydrogen water used in this study and has donated a research division to our institute. Other authors have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)